The Battle of El Alamein

The Battle of El Alamein was a turning point in the Second World War. Australian ground and air forces played an important role in the victory at El Alamein in November 1942. The defeat of the "Desert Fox" Field Marshal Erwin Rommel was the first major allied success of the war.

The RAAF at EL Alamein

"It would be difficult for me to pay an adequate tribute to the work and achievements of the Desert

Air Force; suffice it to say here that the Desert Air Force and the Eighth Army formed one close,

integrated family; collectively, they were one great fighting machine working with a single purpose, at all times with a single joint plan." - Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, Commander Eighth Army

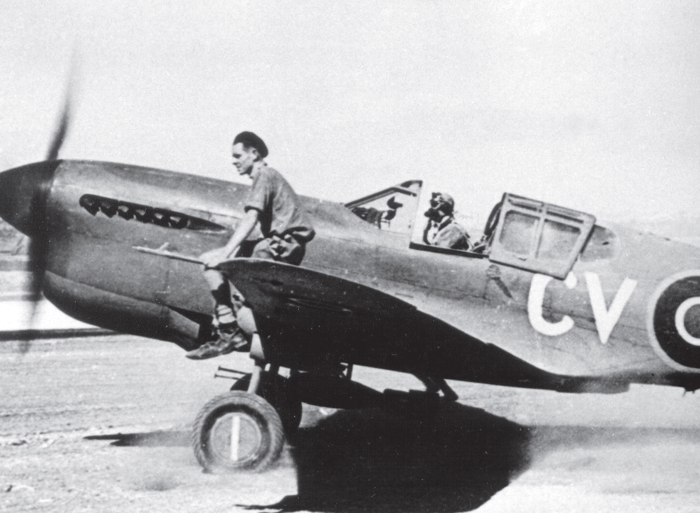

A No 3 Squadron Kittyhawk taxying in the desert.

The Battle of El Alamein was a major turning point in World War II, but it also showed the importance of coordination between air and land forces on the battlefield. It is not often recognised that the RAAF played a significant role in the battle for the air over El Alamein. By July 1942, the Panzer Army Africa, composed of German and Italian units under Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, had struck deep into Egypt threatening the British control of the Suez Canal and the Middle Eastern oilfields. The British Eighth Army defended Egypt and the Canal near a small desert town called El Alamein. Here, in early July, the Axis advance was halted and both sides dug in and began replenishing their forces in preparation for the next major offensive which the British launched under Lieutenant General Bernard Montgomery on 23 October. In preparation for the offensive, RAF Middle East Command shared with the Royal Navy the tasks of guarding British supply lines to the Middle East, and denying the enemy delivery of essential supplies, especially fuel. RAF squadrons, including a number of Australian squadrons, conducted reconnaissance of the Mediterranean Sea. Axis convoys heading for North African ports were subject to attack by aircraft, surface ships or submarines. The interdiction of supplies, particularly fuel, to the Panzer Army Africa deprived Rommel of manoeuvre in the desert war and was a major factor in the Allied victory at El Alamein.

The tasks of maintaining control of the air over the battlefield and attacking Axis ground forces were

allocated to the Desert Air Force, commanded by Air Vice-Marshal Arthur Coningham RAF. Coningham had assumed command in 1941 and set about improving the equipment, doctrine and organisation of the Desert Air Force, gradually achieving air superiority in North Africa for the first time. To provide better air support for the October land offensive, Coningham’s headquarters was colocated with that of the Eighth Army at Burg el Arab, west of Alexandria. Two RAAF squadrons, Nos 3 and 450, flew P-40 Kittyhawk fighter/ground attack aircraft as part of the Desert Air Force in 1942. These rugged aircraft proved highly capable of both air-to-air and air-to-ground attacks. For the two months leading up to the battle, the Australian squadrons were engaged in maintaining control of the air around El Alamein. This was achieved by intercepting any enemy aircraft in the battle zone and by attacking their airfields. On 15 September, 18 Australian Kittyhawks were attacked by 15 Luftwaffe Messerschmitt Me-109s. The resulting dog-fight continued until two squadrons of RAF Kittyhawks joined the fray driving off the Messerschmitts. On this occasion, the Australians claimed only one victim but themselves lost three pilots and a fourth wounded.

On 6 October, heavy rains affected the airfields used by the Luftwaffe but not those of the Desert Air Force which took advantage of the situation to attack the German aircraft that were stuck on the ground. The next phase in the air battle started on 20 October. While Allied ground units moved to positions ready for the planned surprise attack, the Desert Air Force kept the enemy air force from detecting these movements. During this phase, control of the air by the Allies was almost complete and enemy aircraft were rarely seen. When the British ground offensive began on 23 October, the Desert Air Force continued to hold air supremacy over the battlefield. No 450 Squadron intercepted four Me-109s, shooting down two and forcing the other pair to withdraw. Over the next few days, the Australian squadron flew missions escorting British and American medium bombers on attacks against enemy armour and supply lines. When 3 Squadron escorted Allied bombers attacking the airfield at Fuka on 28 October, the formation was attacked by three German fighters. The Commanding Officer, Squadron Leader ‘Bobby’ Gibbes (later Wing Commander Robert Gibbes,DSO, DFC and bar), shot down one and prevented the other two from reaching the bombers. A few days later, Gibbes shot down another aircraft, claiming the squadron’s 200th victory since deploying to the Middle East in August 1940. At the time, this was the highest score among the Desert Air Force squadrons. The Desert Air Force also worked closely with the ground forces to influence the air-land battle. On 26 October, nine Allied air attacks on armoured forces were mounted, three of these being led by No 3 Squadron. On 1 November, with the Australian 9th Division holding

the northern-most sector, Rommel attempted to counterattack with his panzer divisions. Four times on this day, the Australian squadrons successfully attacked these forces by bombing and strafing. In contrast, attacks by Axis aircraft on ground forces rarely succeeded because they were intercepted by Allied fighters before reaching their targets. The Luftwaffe could mount only one sortie for every five flown by the Allies and lacked the strength to effectively defend its own ground troops or airfields. On 2 November, the Australian squadrons were ordered to prepare to advance. The next morning, advance parties were sent forward, at considerable risk, to reconnoitre and prepare airfields with the aircraft following later that day. By 4 November, the Axis armies were in full retreat, with the Desert Air Force in pursuit. The untiring and often dangerous leap-frogging advance of the RAAF ground parties permitted air operations against the retreating enemy to continue unabated. Although only a small part of the Desert Air Force, Nos 3 and 450 Squadrons contributed significantly to the overall air campaign. Over a 34-day period, the squadrons flew 1442 missions, losing 20 aircraft and 16 pilots. Although only claiming 8.5 enemy aircraft destroyed and another 10 probably destroyed, the true testament to their efforts was the fact that air superiority had been maintained over the battlefield for the entire period. The dominance of Allied air power was critical to the British victory at El Alamein. By maintaining control of the air over the battlefield and by denying resupplies to the Panzer Army Africa, the Desert Air Force set the scene for Montgomery’s Eighth Army offensive from El Alamein across North Africa and into Italy. Indeed, the air power doctrine developed by Desert Air Force was used with success during Allied campaigns in Sicily, Italy and Normandy, and it remains the basis for modern airland joint operations doctrine today. (AIR POWER DEVELOPMENT CENTRE BULLETIN - Issue 186, September 2012)