The Fall of Singapore

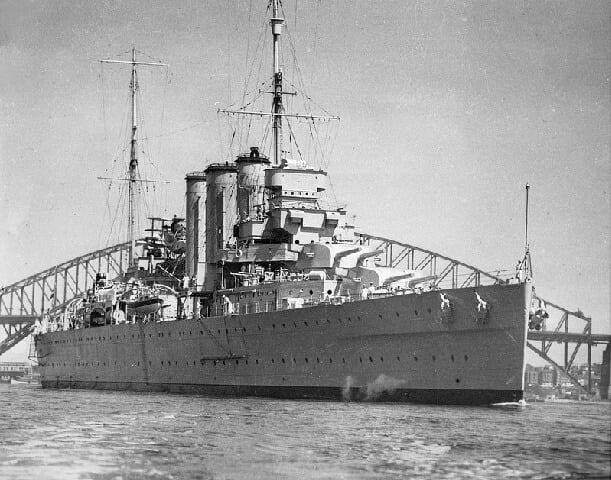

Image: 15,000 Australians were surrended with Singapore

The Fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942 was a crushing defeat for the British Empire. Almost 15,000 Australians were taken prisoner when the island was surrendered to the Japanese. In all, nearly 130,000 troops were captured on Singapore and would spend a torturous three and a half years in ruthlessly administered Japanese prisons and camps. This remains the biggest surrender in British history.

Singapore was considered by the British an island fortress. Winston Churchill, Britain’s wartime Prime Minister called it “Gibraltar of the Orient”. The island’s naval base and Air bases were protected by massive 15 inch guns facing south in anticipation of a seaborne invasion. Beyond the northern boundary—the Strait of Johore—the dense jungle and mangrove swamps of the Malay Peninsula were considered impenetrable for a large attacking force. This small island was a powerful symbol of Britain’s authority in the region and a pillar of Australia’s defence strategy in the absence of a more expensive, independent alternative.

Yet the island’s military capability was never realised. Instead of the ‘great fleet’ promised by Britain for the Naval Base, only a small squadron based around just two capital ships, HM Ships PRINCE OF WALES and REPULSE arrived. Anticipated air power was also never provided. Instead of the 350 to 550 planes promised, only a small contingent, including three squadrons from the Royal Australian Air Force, was based at Singapore. These were no match for the vastly superior Imperial Japanese Army Air Service (IJAAS). Ultimately the RAAF squadrons, and Royal Australian Navy Ships, which had escorted reinforcements to the island, were withdrawn before they could be decimated by the superior air power of the IJAAS.

Japan was determined to neutralise Singapore, which they believed to be a serious threat. They were well prepared for the assault and had rehearsed for months prior. On 8 December 1941 – hours before the attack on the American fleet at Pearl Harbor – the Japanese invaded the Malay Peninsula. At about 0400hours bombers from Saigon launched attacks on the Singapore naval base and harbour. Two days later both PRINCE OF WALES and REPULSE were sunk by Japanese planes off the east coast of Malaya, near Kuantan, Pahang.

The British Empire’s forces on the Malay Peninsula were no match for the speed, aggression and savagery of the Imperial Japanese Army. An IJA force of 30,000, the 25th Army led by General Tomoyuki Yamashita, moved quickly on bicycles, with light tanks in support as well as bombers and fighter planes overhead. They would not encounter the Australians until January, when Units of the Australian 8th Division inflicted significant losses upon them at Gemas and Bakri. Despite these brilliant rear-guard actions, the Japanese, eight weeks after their first landing, had captured Malaya and now stood at the Strait of Johore. The only Australian VC awarded in this campaign was won by the Commanding Officer of the 2/19th Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Anderson. This bespectacled, middle-aged veteran of the First World War was leading a mixed Brigade on a desperate fighting withdrawal. When the force was surrounded he personally led an assault on enemy positions, killing the occupants with grenades and pistol. He was to see over three years in captivity before returning to his farm.

It seemed to those defending Singapore that the advancing force, which had easily swept through Malaya, had superiority – both in numbers, air power and in supply of munitions. Despite the 15 inch guns being capable of firing northward, there were limited shells to provide effective bombardment.

The invasion of Singapore began on 8 February with an intense ground and air bombardment. The first wave of 13,000 soldiers crossed the Strait that evening, in boats, barges and by swimming, and two days later overcame the thinly spread perimeter in the north-west sector. Facing them were Australian soldiers, who were significantly understrength after the desperate actions of the preceding weeks. Nonetheless the attackers suffered heavy casualties, particularly when the 27th Brigade made a stand at Kranji.

As IJA forces pushed into the island, Japanese engineers repaired the causeway linking the Peninsula. Soon more tanks and heavy guns were brought into the attack.

By 14 February the British Empire’s forces, and more than one million civilians, were confined to the city and its immediate surrounds. With the relentless bombardment suggesting the Japanese had shells enough to level the city, and with limited ammunition, dwindling fuel supplies and the Japanese taking controlling the city’s water supply that day, Lieutenant General Arthur Percival, the British commander in Singapore, called for a ceasefire and surrendered. After eight days of desperate fighting, troops, including Australia’s battered 8th Division, were ordered to lay down their arms at 8.30pm on Sunday 15 February. Singapore had fallen.

Some 1,800 Australians were killed in Japan’s push into Singapore. Of the 22,000 Australians captured by the Japanese in those first weeks of the War in the Asia-Pacific more than one third died in brutal and often criminal circumstances.

The base was intended to be a vital link in Britain’s protection of Australia and after its fall, Australia aligned with the United States to defend its interests in the Asia Pacific.

The Fall of Singapore is remembered in a special Australia at War 1942 commemorative series that will be available online in mid March 2017.