Shell Shocked

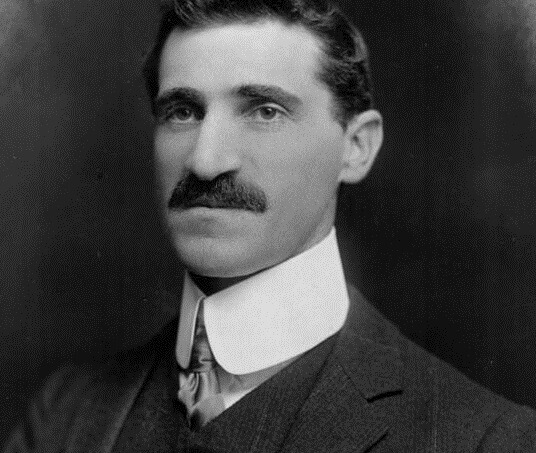

Image: Acting Corporal Allen Jarret, left, with fellow members of the 32nd Battalion in 1917.

“One old man used to charge up the pavement in Swanston Street as if he was doing a bayonet charge. He never hurt anyone but with a ferocious face and an invisible bayonet, everyone knew what was wrong.”

Australian brothers Allen and Thomas Jarrett signed up for duty in 1915, and went to war with the Australian Imperial Forces. Allen was killed in action with the 32nd Battalion near Corbie, France in April 1918 and is buried in the Crucifix Corner Cemetery at Villers-Bretonneux.

His brother, Thomas served with the 27th Battalion, and his service record shows he suffered from ‘shell shock’, not once but six times after serving in Egypt and on the Western Front.

The newspapers of 1918 cited Sir Robert Armstrong-Jones who questioned the attribution of shell shock to cowardice or fear of pain, and pointed out that:

“The human mind is too complex a unit for so simple an estimation…”

Armstrong-Jones also described the treatment of shell shock as “…rather hopeful, as many of these cases are treated successfully with purely mental remedies, like hypnotic suggestion.”

The medical journal, The Lancet, published an article on shell-shock in February 1918. It noted ‘Nothing annoys a nervous patient more than the continual inquiries of his relatives and friends about his experiences of the front’ and advised treating doctors not to allow the patient to dwell on his experiences.

Thomas suffered from shell shock six times in 1916, but returned to duty. He was gassed in the trenches of the Western Front in France in 1917, and was still recovering in 1919 when he was medically discharged. Thomas married Ruth Gould in England whilst recuperating from his injuries and returned to Australia. The couple had two boys and three girl, and Thomas lived until he was 85 years old. He passed away in Adelaide in 1977.

The legacy of shell shock for sufferers is long lasting. A Myers shop assistant in Melbourne recalled her experiences in the late 1950’s, and early 1960’s:

“One old man used to charge up the pavement in Swanston Street as if he was doing a bayonet charge. He never hurt anyone, but with a ferocious face and an invisible bayonet, everyone knew what was wrong.”

“Another used to go into the Myers cafeteria and order two lunches. He would take both to his table, and talk to his invisible mate throughout his meal. He could have had any mental condition, but the staff at least knew what was wrong. He had shell shock.”

Lest We Forget