A WAYWARD TUNNELLER

Image: family portrait of Leonard Harold Francis Fradd

Leonard Harold Francis Fradd was born on the 21 February 1898 in Burra, Hampton District, South Australia. He was schooled at Copperhouse and was the eldest of 9 children born to Francis and Mary Magdalene Fradd (nee Opitz).

The family moved to Broken Hill, NSW sometime after 1907 where they resided in Chapple Street, Convent Hill. He was to have a fairly turbulent childhood. Leonard Harold Francis Fradd was the paternal first cousin of Walter Phillip Fradd. They both grew up in Burra; one in Hampton and the other in Copperhouse.

Little did they know they would one day become brothers in arms in the Great War 1914-1918. Leonard was listed as a Prisoner Discharged Free in the New South Wales Police Gazette in 1915. After being discharged he soon joined the “colours” on 11 December 1915 where he received 6 shillings per day. He stood 5 foot 6 inches tall; this height standard was lowered later in the war as the slaughter of strong young men piled ever higher.

Leonard married Sylvia May Hall in 1916 and they resided in “Cudgegong”, Crimea Street, Parramatta, NSW before he was deployed overseas. The Nominal Roll listed Leonard in the 19th Infantry Battalion, 13th Reinforcements when he sailed aboard HMAT Ajana from Sydney on 5 July 1915 to join the fight.

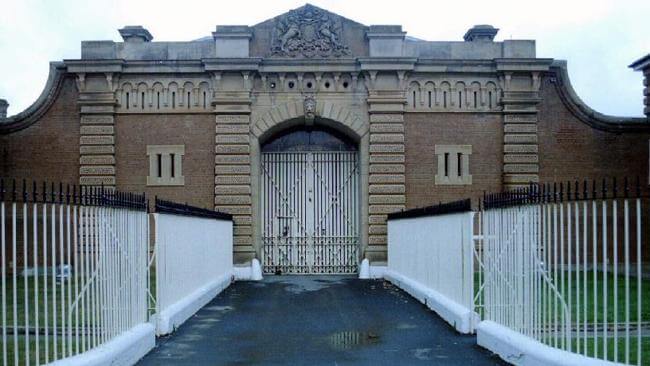

Historic Goulbourn Gaol

Historic Goulbourn Gaol

Leonard was transferred to the 34th Battalion, spent time in the 9th Australian Machine Gun Company and finished with the 36th Battalion. The bulk of recruits, in the 36th, came from New South Wales rifle clubs and, along with the 33rd, 34th and 35th Battalions, formed the 9th Brigade; attached to the 3rd Division AIF.

Upon arrival in England, the battalion spent the next four months training, before taking up a position on the Western Front on 4 December 1916, in time to sit out an uncomfortable winter in the trenches. Many soldiers fighting in the Great War suffered from trench foot and Leonard was no different. He was in and out of hospitals in Belgium and France with this condition.

The infection of his feet was caused by cold, wet and insanitary conditions in which men stood for hours on end in waterlogged trenches without being able to remove wet socks or boots. The feet would gradually go numb and the skin would turn red or blue. If untreated, trench foot could turn gangrenous and result in amputation.

Trench foot was a serious problem in the early stages of the war, particularly during the winter of 1914-15; “If you have never had trench feet described to you. I will tell you. Your feet swell to two or three times their normal size and go completely dead. You could stick a bayonet into them and not feel a thing. If you are fortunate enough not to lose your feet and the swelling begins to go down. It is then that the intolerable, indescribable agony begins. I have heard men cry and even scream with the pain and many had to have their feet and legs amputated." - Sergeant Harry Roberts, Lancashire Fusiliers, interviewed after the Great War.

Over the course of the next six months the 36th Battalion was mainly involved in minor defensive actions. It was not until 7 June 1917 the battalion fought its first major battle, at Messines. After this, the battalion participated in the attack on Passchendaele on 12 October 1917. During this battle the battalion managed to secure its objective, however, as other units had not been able to do so it had to withdraw as its flanks were exposed to German counter-attacks and there was a lack of effective artillery support.

For the next five months the 36th Battalion alternated between periods of duty manning the line and training or labouring out of the line before it was called upon to blunt the German advance during their last ditched effort to win the war during the Spring Offensive of 1918.

During this time they were deployed around Villers-Bretonneux in order to defend the approaches to Amiens, taking part in a counter-attack at Hangard Wood in late March before beating off a concerted German attack on Villers-Bretonneux on 4 April, where the battalion suffered greatly when the Germans attacked with gas.

This was to be the 36th Battalion’s last contribution to the war, it was disbanded on 30 April 1918 in order to reinforce other 9th Brigade units. The earlier campaigns had severely depleted the AIF. in France and since 1916 the flow of reinforcements from Australia had slowly been decreasing as the war dragged on and casualties mounted.

The refusal of the Australian public to institute conscription had made this situation even worse, and in late 1918 it became clear that the AIF could not maintain the number of units it had deployed in France and it was decided to disband three battalions - the 36th, 47th and 52nd - in order to reinforce others.

During its service, the battalion suffered 452 killed and 1,253 wounded. Leonard was wounded and listed on the casualty list with a gunshot wound to the right hand on 4 April 1918. Below the shattered ground that separated the British Empire and German infantry on the Western Front in the First World War, an unseen and largely unknown war was raging, fought by miners. The "tunnellers" as they were known knew that, at any moment, their lives could be extinguished without warning by hundreds of tonnes of collapsed earth and debris.

Leonard would have worked the mines as a prison labourer before joining the AIF, was detached to a Tunnelling Company in Belgium for 3 weeks on the 8 February 1918. These men were engaged in a desperate duel with their German opponents to destroy their opposing front lines by blowing mines, carefully placed in dark, treacherous tunnels under no man’s land.

At the same time the tunnellers worked to defend their own front lines from the German miners, intent on the same deadly task. The secret war culminated in the simultaneous blowing of nineteen huge mines, with a combined payload of almost 450,000 tonnes of high explosives, beneath the Messines Ridge.

Over 4,500 Australians served on the Western Front in the three Australian tunnelling companies and their unique support unit, the Alphabet Company. Around 330 men did from these companies perished. The remains of most lie in carefully tended military cemeteries spread along the entire length of what was the British sector of the front, from the Belgian coast at Nieuport Bains in the north to Bellicourt in the south.

Some lie on German soil where they died in captivity. Others are lost in the dark, silent embrace of the earth and whose resting place is known unto God. Australian tunnelling companies took part in the battles of Fromelles, Arras, Messines, Passchendaele, Cambrai, the defence of Amiens, Lys and finally the famous 100 days that marked the end of war.

Leonard returned to Australia in December 1918. He resumed the life of crime that he left behind after doing six months hard labour in Goulburn Gaol. His suffering as a tuneller and sacrifice in the Great War seem to have only worsened his predisposition to criminal behaviour.